With its alfresco setting and the penetrating echoes of its countercultural themes during an election year in which political disenchantment became endemic, the Public Theater’s revival of “Hair” last summer in Central Park was a unique experience. So shifting it indoors could only dim the thrill, right? Wrong. The enhanced production now at the Al Hirschfeld is sharper, fuller and even more emotionally charged. Director Diane Paulus and her prodigiously talented cast connect with the material in ways that cut right to the 1967 rock musical’s heart, generating tremendous energy that radiates to the rafters.

Much credit goes to the design team’s skill at reconceptualizing the show for a proscenium theater. Suggesting a public space commandeered by hippie occupation, Scott Pask has littered the stage with rugs and splashed sunbeams and stars across a back wall punctuated by windows, doors, walkways and a tangle of stairs. This allows the hyperactive cast to race around at all levels, including aisles, boxes, mezzanine and even street exits.

In a show about community, it’s an astute move to erase the barriers between performers and public, inviting the audience to share directly in both the hedonistic conjuring of peace-love-freedom-happiness and the sorrowful disillusionment that follows. What could have been mere nostalgia instead becomes a full-immersion happening.

The 12-piece band plays composer Galt MacDermot’s period-authentic orchestrations atop a 1950s truck, and a pristine sound mix makes the show as kick-ass loud as it should be, while allowing every one of Gerome Ragni and James Rado’s trippy lyrics and inventory-style poetic riffs to be heard. The most dazzling new contribution is visual magician Kevin Adams’ lighting, alive with throbbing colors that truly pop and psychotropic effects that make the walls, floor and ceiling swim.

Yet despite all the creative and financial resources applied, there’s no trace of deadening slickness here. The show still has the loose vitality of urgent, spontaneous expression, thanks to a vibrant ensemble that understands the guiding principle of deep-rooted group harmony while still asserting distinctive personalities.

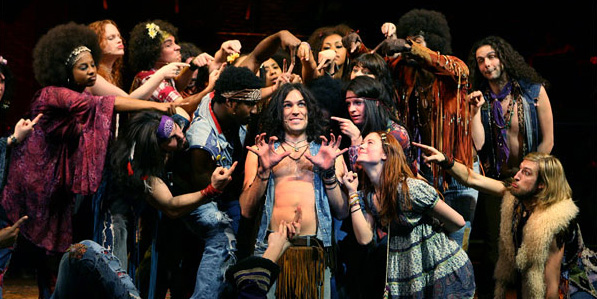

The production’s veterans have honed their characterizations into second skins: Will Swenson’s Berger is a fiercely charismatic ringmaster, his cheeky audience interaction banishing spectator detachment from the start. Darius Nichols’ Hud has a sexy strut and deadpan insouciance; Bryce Ryness’ Mick Jagger-loving Woof drolly balances swagger and sweetness; Allison Case’s Crissy beams raw vulnerability and idealism; and Kacie Sheik’s pregnant Jeanie nails the flaky comedy and the ache of unrequited love.

Among newcomers, Gavin Creel’s assured singing and unforced charm are a fine fit for the doomed Claude, and he establishes a warm bond with Swenson’s Berger, the pair of them firing up the rousing title song. Creel brings rebellious self-affirmation to “I Got Life,” darkens the tone via the confused questioning of “Where Do I Go,” and amplifies the bitter poignancy of “The Flesh Failures.”

Also a strong addition, Caissie Levy’s ballsy Sheila is persuasive as the group’s galvanizing political force, pumping wounded anger into “Easy to Be Hard.” The one disappointment is Sasha Allen as Dionne, a marginal character given major vocal duties, notably on “Aquarius,” “White Boys” and “Walking in Space”; she sounds too contemporary, layering on intrusive “American Idol”-style growls and warbles.

Draped in Michael McDonald’s flower-power finery, each Tribe member gets multiple opportunities to shine, and while one or two of them stretch age-appropriateness a bit, the overall impact is of a group bursting with youth. They elevate the audience to such a collective high during the first act’s nonstop exuberance that the apprehensive turn becomes all the more wrenching.

Paulus rises to the challenge of shaping Ragni and Rado’s freeform vaudeville collage into a narrative, particularly in the heartbreaking crescendo of the final scenes. And Claude’s extended hallucination suite, which often drags, here walks a mesmerizing line between humor and horror.

The characters’ unity of spirit is mirrored in their movements as choreographer Karole Armitage shepherds the group into a writhing mass, a sinuous human chain or splintering comets. Her brilliant work has the appearance not of practiced steps but of uncontainable physical self-expression.

Surprisingly, considering how firmly they were rooted in the zeitgeist of the era, the songs remain trenchant. The score’s vigorousness and variety are remarkable, threading together delicate melodies with driving, combustible ones, double-edged comic sketches with celebratory anthems, dirty funk, hippie-dippie lovefests and satirical ditties.

Fears that the Vietnam-era show’s message, which struck such a chord in the waning days of the Bush administration, would have less impact in the Obama age now seem unfounded. While it’s unmistakably a period piece, “Hair” plays almost like a direct response to the fallout from a culture of shortsighted greed.

Following the exit of “Rent” and “Spring Awakening” from Broadway, a vacancy exists for a rock musical that communicates viscerally with its audience. This revival does that and then some; it’s likely to invigorate kids coming fresh to the material as much as baby boomers disinterring memories of their youth. If this explosive production doesn’t stir something in you, it may be time to check your pulse.